Only practitioners left alive. Interview: Thoughts on diversity, intangible and living cultural heritage.

There is a thin red line between a living and dead tradition, sharing and stealing, change and memory, diversity and unity, or obsessively protecting while making any culture available. An the thin red line can even look like seal skin. What makes intangible cultural heritage the hot topic of today for everyone – from careful safeguards and careless globe-trotters?

We begin a series of articles dedicated to the ongoing NORTHERN DIMENSION PARTNERSHIP OF CULTURE: CREATING NEW PRACTICES OF SUSTAINABILITY project (that CAPITAL R will cover during the next following year) with an exclusive discussion from the “Living heritage in the Nordic countries” conference that took place in Espoo, Finland, from 31.10. – 02.11.2019. A conference gathering more than one hundred professionals from all across the Northern Europe and the Arctic – from Lithuania to Greenland, from Denmark to Sápmi (with participants from NGOs, museums, educational or research facilities to governmental institutions or avid practitioners), who try keeping traditions at good health according to the UNESCO’s Convention “for safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH)”. It’s a document adopted in 2003, ratified by 178 states as of today, and defined many activities during the conference.

Invited by TAIKE (Arts Promotion Centre Finland) and supported by NDPC (Northern Dimension Partnership of Culture) in Latvia, CAPITAL R had an exclusive chance to talk with two important participants of the event. They were: one of the most knowledgeable minds on the Convention Eivind Falk, also director of Norwegian Crafts Institute, and one of the most vocal researchers of Greenland’s history and indigenous heritage, Kirstine Eiby Møller, also working as a curator at Greenland National museum and Archives.

Sitting in a rest room before the sauna at the conference venue, we talked, and with this transcription of our discussion, touching multi-layered, difficult and even contradictory topics, including not a single right solution, we began to uncover this international project bit by bit. A project that “focuses on exploring the problematics of sustainable development experienced by communities in the Northern Dimension area from the perspective of the arts based on the four pillars of sustainability” – social, cultural, economical and ecological.

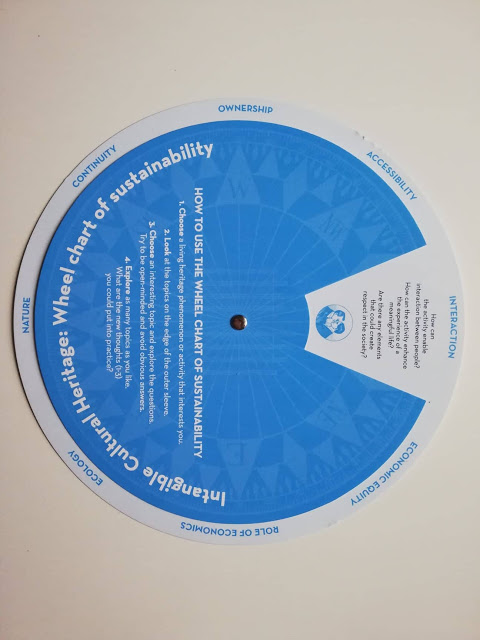

When entering the premises and registering for the conference, every participant received an interesting artefact – the “Wheel chart of sustainability”, developed as a part of the project. Although created as a tool to implement the UNESCO Convention on the Safeguarding of the ICH in Finland, it gave a better, universal idea on how to construct this conversation too. After all, the eight topics covered on the wheel (ownership, accessibility, interaction, economic equity, role of economics, ecology, nature, continuity) are important globally for both the tangible and intangible.

CR: At first, I would like to ask you if there might be a particular and uniting reason that brought us and no one else here (talking about a geographical region north of Central Europe). After all, there might be some cultural similarities that unite us. Let’s put it like this – many people from the south talk about some kind of northern temperament, so there is an element that defines the north more than others. I also asked that question to myself and sometimes I think we might know the bathing and sauna culture a bit – from Latvia, across Finland and all the way to Iceland’s hot tubs. But one thing, more unique to that, might be our understanding of darkness. And I believe every person in the north might know how to use it or cope with it better, and might have managed to even enjoy it. What elements do you think could define the Northern European culture?

K: First of all, Greenland should not be counted in as Northern Europe, and I can also feel it at the conference. I maybe see some things common with the Sápmi, but I definitely only feel Arctic compared to here. Sure, Greenland probably does have something to share with Northern Europe, since it was colonized by the Danes for a long time, and trough Denmark we usually have ties to Norway, Sweden, Finland. But, even though many people have stressed that we have many things in common, what I noticed here in Helsinki were the differences; but I mean that in a good way. I felt that I am definitely in Finland, not in Denmark, although it’s quite flat in both places!

E: I am not sure we need to find anything that unites us at all. If you use the ICH Convention, there is a term “community” that is actually mentioned 25 times on the application form for the representative list alone. For five questions! So it is crucial to the whole process. I have been in the evaluation committee for four years, and what I see is that, the more you try defining a community, the more difficult it becomes. For example, you have three traditional makers of wooden skis, say, in Norway, Latvia and Greenland. So they come together, fill out the form and go for a multi-national nomination for the representative list. They all connect to each other, or they have some representative for the group, but when something gets thais big, it’s very hard to maintain the unity. It’s like the sauna nomination in Finland – they say that, out of 5,5 million people in the country, 5,4 million take sauna. So it is one sauna community! But how can they give the letter of consent? Who will represent them? How will they prove that this is a common interest to everybody? So, when you ask about the uniting culture of the north, is is very difficult to answer. Maybe blacksmiths have something in common, maybe ski makers, maybe Sápmi people have connections of traditions in Finland, Norway, Sweden and even in Russia, but to find one thing that unites us all… It is actually against the spirit of the Convention that tries to promote diversity. Why do you want to find something in common?

CR: I believe that if we must also find pinpoints of unity rather than differences, it is very helpful. There was a reason that the European Union was created – to avoid future conflicts between different nations.

E: Yes, but I believe conflicts have not much to do with the diversity. After all, you don’t have to water flowers the same way, or eat with the fork the same way to have respect of each other. But, on the other hand, many elements of culture might not need to be of a national ownership. In fact, if it’s a living heritage, it must travel around.

CR: Do you think there’s someone who owns such cultural elements?

E: Do you know El Cóndor Pasa, a song by Simon & Garfunkel? It has been used as an example, when they took this song from indigenous people from South America and made a big world hit out of it. But who has the ownership to it? Did any money Simon & Garfunkel earned made it to the the indigenous community*?

CR: Is it generally okay if they only appropriated the melody and if it's another example of this living heritage that travels around?

K: I think appropriation is never okay. There is a huge difference between being inspired by something and stealing. When you take something from indigenous people without any acknowledgement to the culture or any way of appreciating it, then you are just hurting people that have been hurt for many, many centuries. Of course, any nationality can appropriate from any other as long as you don’t step on anyone. I’m talking about another sort of “intangible culture” I would like to see dying out, and that is colonialism. We need to respect the fact – when some communities feel ownership of something, they don’t want to share.

CR: How can we be totally sure they don’t want to share it? If someone buys an old record somewhere, and there are songs without copyrights, then who is to stop them from using that material? Even when there is any ownership, if the author has died 70 years ago without any successors, anyone can legally use the work.

K: It depends. If we are talking about sacred songs of indigenous people, do they ever stop being sacred? When discussing about ICH, I believe you only own something if you really practice it.

E: That is why the Convention starts with community. If they are the ones sharing any element, they have the ownership over it. It is crucial to the Convention, and shows a good way to respect any community.

CR: What about recipes? Many of us eat things that were created across the globe even several centuries ago, and who could tell if any of the nations have their ownership purely? Recipes usually stand as a representation of sharing and even stealing, say pasta (Italians from Chinese) or bread.

E: Two hundred years ago there were regulations in Norway that instructed who can bake bread, do silversmithing, jewellery, make furniture and houses. Craftsmen had strong organizations, if you tried to do any of the given things on your own, you could be arrested. I agree that today there could be cases of taking ideas from others, but I believe there are still many traditional crafts that are too complex to be stolen entirely, for example, boat building. It takes several years to learn it, and you need somebody, who can teach you and with whom you are in good relationship. Many communities are happy if someone is very eager to learn their traditions, although it can cause many problems too.

There were studies done in Uganda, where part of their traditional herbal medicine is based on leaf extracts. But now there are big pharmacy companies that learn the trade and make patents for this medicine, they claim its ownership and leave the natives with no rights.

CR: Meanwhile, according to the law, there is really nothing to protect those tribes.

E: That’s right.

CR: It's terrible to hear it, but the paradox here is that, if the community keeps a tradition, it is maintained the way it was planned, but if one wants to promote their heritage without eventually dying out, one must also take risky measures to make it accessible to the public.

K: I disagree. You are talking about the accessibility of elements to all humanity. But then why are there differences between communities and cultures? What makes a culture different? It’s a particular way of expressing, navigating, understanding.

CR: But all elements are still accessible, everybody can try approaching them.

K: Not necessarily. The difference between you and me, for example, is that you could never see the world the way I do. There are some parts of my culture that’s always inaccessible to anybody else.

CR: But what if someone really falls in love with you, creates a new family with you and lives in Greenland the rest of his life, and you both live long lives, say 90 – 100 years, and he really is into your culture, really wants to learn every single bit? You have children, and he even denies everything he’s been before. Do you still think he might not have rights to reach for every element and tradition your community can share?

K: Of course he can learn all of it, but he will never experience everything the way I do. And I also think it would be so horrible, if any person would give up their entire culture to be with someone else. It’s what grounds us, and when we start to displace people from their culture, they are hurt. Of course there are people in Greenland, who want to be identified as a part of something else when they re still not born in the culture. But, when kids are born in a culture, they are completely shaped by the worldview subconsciously. That makes the difference between them and this hypothetical man, who might learn and indulge into my culture, but will never really understand it.

CR: Would you understand your children in 20-years time?

K: Probably not.

E: But nothing of that stops you from learning any elements of ICH that you believe connect us as communities. If you are dancers, you can learn other dances, too, understand their meaning over time, their social and emotional function in the community. But there are other elements, rituals, contexts and their meanings, for example, in Ethiopian culture, that could be really hard for any white person to even understand. On the other hand, I don’t think there’s any obligation to learn an element at all. Sometimes it just takes too much time to learn it and might take too much to understand the element just like that.

CR: But I still insist there should always be a possibility to learn as much as I can.

K: That is true. But there are some things that might not be accessible to you not because of people not willing to give something away, but because you are not grown up with it. For instance, do you feel comfortable with silence? A lot of people don’t. But in Greenland we can sit together, not say a word for hours and still enjoy ourselves. And then others might enter the room and say that, oh, it feels like tension, people are too silent! And then, depending on what culture you are from, it might also be impolite to ask – what if they were fighting?

E: Sometimes we wrongly decontextualize cultural elements in order to try to learn them. Alright, we all can learn how to knit socks. But very often, if you read or watch the documentation, it still doesn’t give us the whole context, a broader view of the real function behind each ornament or the whole process of why we knit. I have an example on how Sápmi people are stopping blood. Some time ago I attended a conference and participated in some traditional Sápmi crafts. I chose to work with seal skin, and, as you probably know, it’s very thick. The needles to work with it are shaped in a special way and very sharp. Like a blade. And, accidentally, I cut a little piece of the top of my thumb that started bleeding. I put the plaster on, but it continued to bleed when I started working again. I struggled with this for one and a half hours, when suddenly this Sápmi woman in her dress appeared after observing me. She took the needle I cut myself with, dragged it over my wound and said some mumbly, indistinct words, and it stopped bleeding! And then, before I managed to say “thanks”, she took my thumb and said – you know you have a very strange colour of your blood! It was an interesting encounter that I forgot after a while until later that night when returning to the hotel to meet other people, who attended the conference. They asked me why I was late, so I told them the story and, when I needed to show the thumb for proof, it turned out there was nothing wrong with it! It was totally healed! Two years later I was there again for another conference and suddenly saw the same old, short lady standing behind the curtain. I went over to her and asked if she remembers me. When she was unsure, I told her the story about this thing with the thumb and asked if she can teach me how to do this because it is really useful to learn how to stop blood! And she said – “Well, I could do that, but it will, most probably, take two years, you will have to live with me, with the reindeer, in our tent just to understand the nature, how things are working here.” So, you cannot decontextualize the element, take a piece out of something and think you can understand it.

CR: By using this example, you touched another two topics on the “Wheel chart of sustainability” – ecology and nature. And today, like it or not, many traditions, especially near maritime regions, are eventually going to extinct. That one element, fish or sea food, disappearing will affect fishing culture, also traditional crafts related to endangered species, say, Polar bears, might mean that many intangible practices will die out. No doubt, we are to blame ourselves, most of nations only start thinking about overfishing problem when we have caught too much. The question is, though – can we maintain some of the endangered traditions if we know they are on the brink of extinction globally?

E: At first, ICH or traditional crafts are, maybe, the most sustainable way to protect while producing. Instead of using machines, they use traditional materials, tools, techniques, are a good physical activity, are much better for the nature, consume less energy, and, in most cases, the practitioners also appreciate the source of nature.

K: The way I see it (and the way I was brought up to think) is that, if no one has any interest in any practice, it has lifted its course, including colonialism. I was on a meeting last year with a lot of American scientists, all talking about the grimness of melting ice and how it destroys archaeological sites in Greenland and their science. They asked me to talk about ICH and, unlike them, I was not scared about anything dying out.

If no community wants to keep the practice alive, I’m not going to force it on anybody, but I will at least record their last saying so we have it in the archives, proving it once existed. Call it an organic view.

E: That is again the ownership of the community. Eventually, it is not an expert or professor at university that decides, what is important and what is not, and it’s the choice of the community, nobody else’s. If a tradition is broken then, according to the Convention, it is not regarded as ICH any more.

CR: But then again there are examples of languages like Livonian that died out in most parts of Latvia not because of the community being interested in practising it no more. It died out because of, in this case, the Great plaque epidemics (1709 – 1711) and its aftermath on human count, literally killing almost every Livonian speaker in the largest part of the country. It died because of unforeseeable circumstances. Or the tradition of horse keeping. We had hundreds of folk songs about the relevance and meaningfulness of ploughing fields, but it’s been more than 50 years since they mean nothing to most of people, and horse breeding is something exclusive nowaydays. How should we feel about the people loosing their tradition? If they are fishermen asking for subsidies in the near future (especially when they are not related to any ICH, but rather pure industry), should we support them if we know that there might not be any fishing allowed in a few years time? When is the moment when the community says – we have decided we don’t need this tradition, there is no interest from younger generations, there is no demand, we don’t consume this any more or there is nothing left to consume? I believe it is never easy to say it, especially to the last ones physically and emotionally attached to it for all their lives, believing they practice the tradition at their best intentions.

K: I believe we have the ability to revitalise traditions. Of course, it wouldn’t be the same thing, but nothing is ever the same thing. The way we do knitting today is very different to what it was even 100 years ago. For instance, a century ago tattoos completely died out in Greenland, they were banned because of the Christianity. Today, if you go to Greenland, you will see so many men and women carrying tattoos and finding strength in them. Not because they are not Christians any more, but because we are able to express a part of our culture that was forbidden by others. We might have lost the exact meanings of the symbols, but what they mean today are still important to our culture. So, yes, I do believe, when the time comes, we will always revitalize traditions.

* In 1913, Peruvian songwriter Daniel Alomía Robles composed "El Cóndor Pasa", and the song was first performed publicly at the Teatro Mazzi in Lima. In 1965, Paul Simon heard for the first time a version of the melody by the band Los Incas in a performance at the Théâtre de l'Est parisien in Paris. Simon became friendly with the band, later even touring with them and producing their first US-American album. He asked the band for permission to use the song in his production. The band's director and founding member Jorge Milchberg, who was collecting royalties for the song as co-author and arranger, responded erroneously that it was a traditional Peruvian composition from the 18th century. Milchberg told Simon he was registered as the arrangement's co-author and collected royalties. In late 1970, Daniel Alomía Robles' son Armando Robles Godoy, a Peruvian filmmaker, filed a successful copyright lawsuit against Paul Simon. The grounds for the lawsuit extended that the melody had been composed by his father, who had copyrighted the song in the United States in 1933. After the lawsuit Armando Robles Godoy said that he held no ill will towards Paul Simon for what he considered a "misunderstanding" and an "honest mistake", admitting that Paul Simon is very respectful of other cultures. It was a court case without further complications. In regard to the Simon & Garfunkel version, Daniel Alomía Robles, Jorge Milchberg, and Paul Simon are now all listed as songwriters, with Simon listed alone as the author of the English lyrics. Wikipedia.com